At this point he had built quite a following, and after years of turning down offers to exhibit his work, legal bills forced him to reluctantly agree to get into the art business and make money. Fischer hated the spotlight almost as much as he hated the police, and felt he was selling a bit of his soul by exhibiting his work for people who, a few years earlier, would openly criticize graffiti artists like him. But lawyers cost money. That was nevertheless a turning point for him: instead of erasing his tags Hamburg started to look at them with pride.

OZ died a Thursday night of September 2014. The paint from his last tags was still wet when the police found his lifeless body along the tracks of the S1 Line, between Berliner Tor and Central Stations, 45 odd minutes after a commuter train hit him. He was 64.

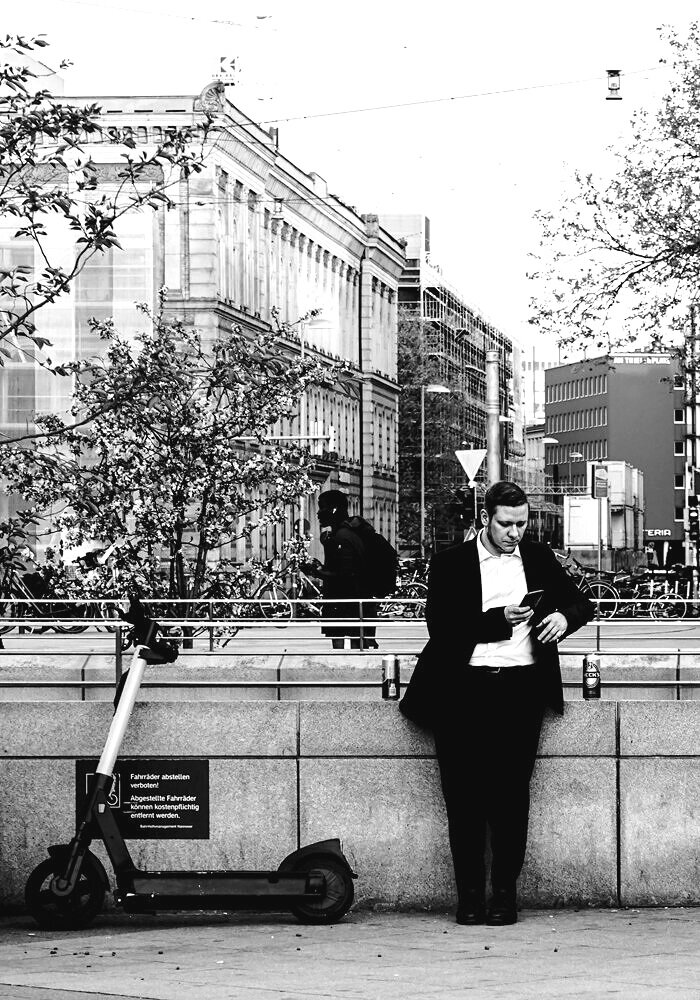

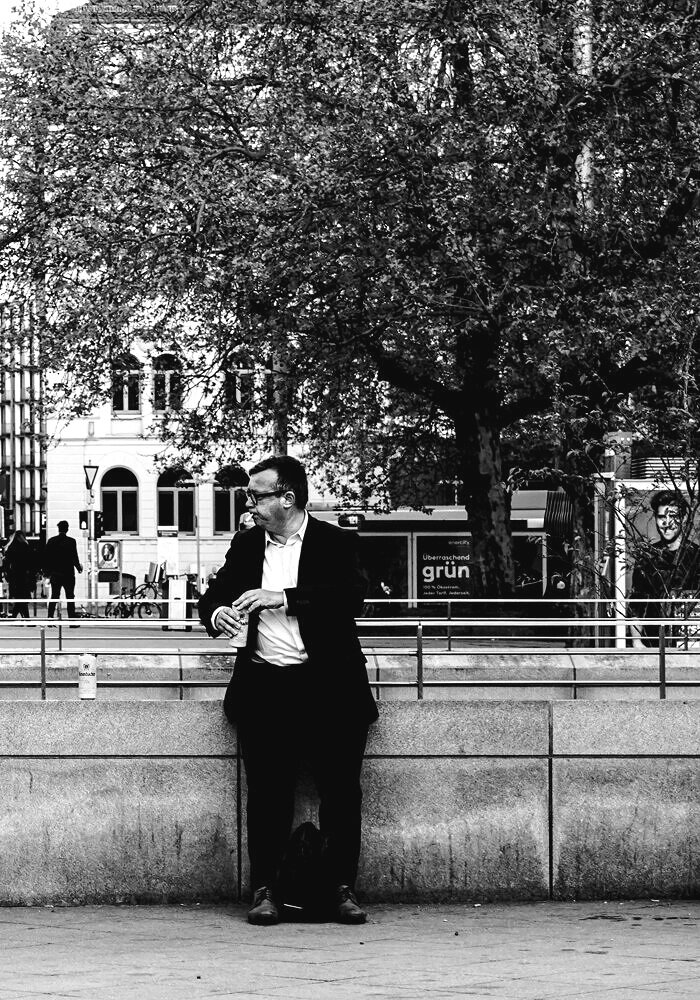

To say that his art outlived him would be a bit too simplistic. Most of his larger colorful murals are already in poor condition, although his simpler black-on-white or white-on-black tags have held up pretty well. Hamburg has indeed turned into one huge “find the smiley” playground. Yet what has changed in Hamburg is the overall attitude regarding graffiti, and OZ’s cheerful graffiti played an important part in that reassessment.

Graffiti is undergoing a social reassessment, from visual pollution to proper art form, and is increasingly gaining the mainstream support long enjoyed by mural artists. There’s an unwritten code about tagging over someone else’s work, or defacing a heritage building, and as long as taggers abide to it, the public will keep of getting more supportive. Some neighborhoods such as St. Pauli and Sternchanze have even taken on to graffiti, to the point where every surface within reach might get painted. Guys like OZ have certainly made cities like Hamburg more colorful, and transformed the way we see our urban environment. These are no longer bare concrete walls, only blank canvases.